|

|

Sam M

·

Mar 29, 2025

·

Sydney, NSW

· Joined May 2022

· Points: 1

I rediscovered John Ewbank's amazing and very long lecture "Ironmongers of the Dreamtime" transcribed on the Supertopo archive. http://www.supertopo.com/climbing/thread.php?topic_id=2292864&tn=0 All of it is worthwhile, but I especially wanted to quote his thoughts on why exactly he decided to invent a new grading system for Australia. ----- When I wrote my guidebooks to climbing in the Blue Mountains, I was so appalled by the uselessness of the English system and the confusions of the European systems that it seemed best to just dump the lot in Sydney Harbor and start again. For example, the top English grade at the time — “extremely severe” — could include anything from riding an escalator to finding yourself on an overhanging greasy nightmare with no visible holds and nothing for protection except a tied-off twig.

Other examples? For a start, the grading systems being used in other countries all had an inbuilt and totally unrealistic glass ceiling, which tradition made it impossible to change. Furthermore, they were all using subdivisions, which created false psychological barriers. And, finally, they were not working well in their country of origin, so why the hell should they work half a world away? An important aspect as well was Australia’s great isolation from what was then a Eurocentric focus in world climbing, and especially a British focus. Because a trip to England was out of the question for most Australian climbers, there was a constant state of confusion about grading climbs at all. So we had the strange situation of climbers in Australia putting up climbs and not being able to grade them because the frame of reference for doing so was 12,000 miles away! Of course, climbs were graded, using the same system as in England, but lurking beneath this was the constant question, “But what would this be graded in Wales or the Lake District?”

What we needed was something simple, and more importantly, something that was consistent and our own. So I started a new grading system, beginning at 1 and proceeding one number at a time, with no subdivisions and no pre-ordained limit.

My reasons for starting the grades so low came from a desire to demystify and redefine the point at which climbing starts. There exists to this day the fallacy that climbing has to be difficult and is in some way a specialized activity that needs truckloads of shiny things. I simply wanted to start with the basic activity of walking uphill as being grade 1, and to let the hill get steeper at its own pace. To pretend that there is a magical and definable point at which walking ends and scrambling begins, or scrambling ends and “real” climbing begins, is just plain foolish.

I never liked the old adjectival way of grading climbs because it implies that there exists a universal criterion of ability. In other words, the guidebook writer, or whoever, is to some degree predicting the experience the climber can have, or should have, on a particular climb. When I was nineteen I worked as a climbing instructor for the Manchester Education Department. Most of the kids were in their mid- to late teens, but sometimes we’d get groups of little ones. Instead of taking them to the cliffs, we’d just take them out hill-walking the moors. But I often thought that if we had been allowed to take them climbing it would have been a pity to tell them that what they’d struggled up was graded “Easy.” Similarly, when I tried to make a living instructing climbing a year later in the Blue Mountains (a doomed and futuristic endeavor, that, if ever there was one — talk about optimistic), I was never too thrilled to be telling someone that what we had just climbed had been “Mild severe,” when to them it was maybe the most intense thing they had ever done.

One thing I was vocal about at the time was to emphasize that the system should be thought of as open-ended from the word go, and not be thought of as in any way having a ceiling. I wanted to ensure that what was being done should not be interpreted as any indication of what was possible.

One criticism of the Australian system is that there are too many numbers. But take away 1-7, which are there for small children and total beginners, and what remains is comparable, more or less, to the total number of subdivisions currently used in England and the U.S. Not that this is in itself any justification — to follow these countries simply because they have thicker, glossier, and more expensive magazines, and a bigger population of climbers, is no guarantee of anything at all.

A more pertinent criticism is that the grade doesn’t take factors such as loose rock, length of climb, quality of protection, and seriousness into account. My response to this was and still is: “That’s what words are for.” It is interesting that the British climbers, historically a literate subculture in a traditionally literate country, should be leading the gang worldwide in the mumbo-jumbo-mystification steeplechase. No combination of numbers, letters, and symbols will ever convey information as accurately as words when it comes to describing these factors of a route. If on the fourth pitch there is no protection for sixty feet, what is the problem with saying, “On the fourth pitch there is no protection for sixty feet”? If the climb is very sustained, why not try communicating this piece of information by using words such as, “The climb is very sustained.” Does anyone need to be told by a complex series of symbols that a ten-pitch climb ten miles from the closest road is going to be a different outing than a one-pitch climb on a roadside crag? Have these Poms been using too much vinegar on their fish and chips? Not enough? Too much salt? What is the problem here?

And a final comment on this subject: What’s wrong with leaving the guidebook in the bag? Give yourself a thrill! Bring back “the four Fs,” as I and my old mate Alec Campbell used to recite to each other: “Fail on it, Fall on it, or Fly up the F*#ker.” ----- RIP John.

|

|

|

Alan Rubin

·

Mar 29, 2025

·

Unknown Hometown

· Joined Apr 2015

· Points: 10

Excellent commentary. Thanks for 'excavating' this Sam. I look forward to reading the entire essay when I have a bit more time. I know that Steve Arsenault, who posts on here occasionally, had the opportunity to climb with Ewbank in the late '60s and remained in contact with him. I believe that Ewbank spent the last part of his life living in the US ( NY?), but I don't think that he ever climbed here. He was clearly a very clear-headed, articulate, and creative individual. Sam, is there any way that you can repost the link to the original essay so that it is 'clickable'.? Thanks.

|

|

|

stephen arsenault

·

Apr 2, 2025

·

Wolfeboro, NH

· Joined Aug 2011

· Points: 67

John Ewbank was perhaps the most memorable climber I ever climbed with. He had a unique personality, with extreme highs and lows, and I didn't learn until after his passing that he was bi-polar. He never knew his parents and was adopted. I climbed with him in Australia, and years later in New Hampshire just a year before his death. He was gifted in so many ways as exhibited by his climbing, writing, and composing of music, and verse. One of my vivid memories is encountering a huge Huntsmen Spider, while leading the crux pitch, on one of his routes on Dog Face, in the Blue Mnts. Here is a photo of John on his classic route- Genesis-circa 1969.

|

|

|

richard aiken

·

Apr 2, 2025

·

El Chorro Spain

· Joined Nov 2008

· Points: 20

John set routes at some Manhattan climbing gyms where I climbed in the late 1990s. He would be hanging upside down while singing Australian ditties. Always helpful to me as a beginner. Definitely a character.

|

|

|

Noah Betz

·

Apr 3, 2025

·

Beattyville, KY

· Joined Nov 2017

· Points: 49

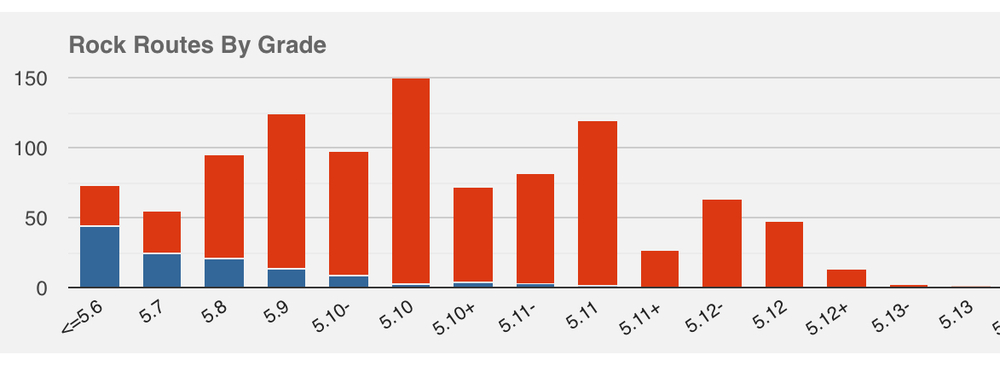

Great find, I enjoyed reading it. Re specifically to this point- > Furthermore, they were all using subdivisions, which created false psychological barriers. Genuine question to Aus climbers, is this actually accomplished by the Ewbank system? From the outside looking in, it would appear to me that it would just arbitrarily shift the ‘barriers’ to whatever grade the ‘pleasing number’- for lack of a better term- is. Using the standard conversion chart, I would wager that training for and sending your first 20, 25, and 30 are major milestones in an Aus climber’s career, similar to how 11a, 12a, and 13a are ‘chased’ grades in the YDS system. This is pretty noticeable at the red, where visiting Europeans will commonly be looking for a 13b (8a) to send during their visit and defer on commonly chased 13a (7c+) routes, largely because the 13b is the ‘pleasing grade’ in the Font system. I won’t pretend that this psychological effect of pleasing grades doesn’t affect me and the routes I, partially subconsciously, partially not, choose to get on. Here’s my current grade pyramid, which consists of almost every climb I’ve been on outside since 2017: The pleasing grade effect is pretty noticeable on the 11+ column, though this is partially due to there being more 12a routes than 11d routes in the red. Do Aus climbers have a similar artificial dip at the grades prior to ‘pleasing grades’, like 19, 24, and 29?

|

|

|

Sam M

·

Apr 3, 2025

·

Sydney, NSW

· Joined May 2022

· Points: 1

Noah Betz

wrote:

Great find, I enjoyed reading it. Re specifically to this point- > Furthermore, they were all using subdivisions, which created false psychological barriers. Genuine question to Aus climbers, is this actually accomplished by the Ewbank system? From the outside looking in, it would appear to me that it would just arbitrarily shift the ‘barriers’ to whatever grade the ‘pleasing number’- for lack of a better term- is. Using the standard conversion chart, I would wager that training for and sending your first 20, 25, and 30 are major milestones in an Aus climber’s career, similar to how 11a, 12a, and 13a are ‘chased’ grades in the YDS system. Good question. Grade 25 is certainly a milestone, especially because it's around the V5/5.12 range that is such a common plateau. It's funny because I was going also going to list some other Ewbank grades that are milestones. But then I was thinking, my first 19 was cool, and my first 20 on gear I remember, and 21 of course, my first 22 at Nowra I'm fond of, 23 is a classic grade, then 24 was like my first real project....so maybe the Ewbank system does accomplish this goal! What's mildly interesting, the Ewbank system kind of lines up with human age, and it turns out that Grade 18 and grade 21 often seem to be milestones as well. It's actually common for people to try and keep up with "climb their age" through their 20's. By the time you get to grade 30, you're a serious sport climber so people are usually thinking in terms of French grades half the time anyway (exactly the cultural cringe Ewbank warned about!)

|

|

|

richard aiken

·

Apr 9, 2025

·

El Chorro Spain

· Joined Nov 2008

· Points: 20

Noah, if you want to hear from climbers in Oz, you could post on Chockstone.org for Victoria which has a lot of knowledgeable and long time climbers on it and I think there is one for NSW climbers too

|

|

|

Sam M

·

Apr 9, 2025

·

Sydney, NSW

· Joined May 2022

· Points: 1

richard aiken

wrote:

Noah, if you want to hear from climbers in Oz, you could post on Chockstone.org for Victoria which has a lot of knowledgeable and long time climbers on it and I think there is one for NSW climbers too Unfortunately, Chockstone is totally dead, gone with Supertopo and RC.com to the great internet climbing forum in the sky. That's why I post here! Better off posting on theCrag.com

|

Continue with onX Maps

Continue with onX Maps Sign in with Facebook

Sign in with Facebook