Trad fall at Indian Creek Crag RRG 4-27

|

|

Eric my understanding is that constraining the rope side biner acts to mitigate some of the chaos and unpredictability referenced above that can result from the rope whipping around in a piece pulling fall (and to a much lesser degree in more common climbing situations) -a constrained biner is more likely to be loaded in the orientation you placed it in rather than getting whipped around and loaded in a different, possibly less safe orientation (ie become nose hooked or cross loaded etc). |

|

|

I have some experience using double (half) ropes. The upthread suggestion that this might mitigate the piece-pulling-chaotic-rope behavior scenario seems worthy of serious consideration. A leader might get the best of both lines of thought. And Nowhere, thank you for your post. I appreciate it. Especially if a cordial, intelligent, and adult discussion ensues. |

|

|

Not much interest in addressing the root cause of the issue here. ??????????? |

|

|

Hi Eric, I realize this comment may be interpreted as a snarky rebuttal so let me emphasize that my stance is a cordial disagreement about the level of interest in root cause analysis of the incident. Here’s what I’ve gleaned from the root cause analysis so far: It sounds like the top piece pulled and unclipped. Maybe it was a poor placement (placed blind or while pumped out) or got kicked by the climber, etc. the broken carabiner was most likely loaded over an edge or nose hooked and the belayer has thoughtfully chimed in stating it was unlikely to be over an edge. The third piece unclipped but stayed in place, so chaotic rope movements after the above pieces failed is the most likely factor. Possible solutions include locking carabiners on critical points, extending carabiners away from edges, and using double ropes to limit vulnerability to chaotic movements and extra slack due to ripped gear. As for nose hooking, it remains unclear if reducing degrees of freedom at the rope side carabiner increases or reduces risk, and it is likely that some carabiner models are less prone. I think we’re limited to conjecture and opinion on this point unless someone has done experiments. I think this has been a very productive root cause analysis. |

|

|

Eric Craig wrote: Hate to burst bubbles, but 99.5% of all climbing accidents are due to user error. The two folks involved in this accident are going to have to focus on their inner self to answer and learn from what really happened. |

|

|

Leif Mahoney wrote: My purpose here is to encourage a useful conversation. There is OLD technical information that sheds some light on this subject IF at least a few people can change their focal point.

Other than the falling off part, protection failure is the root cause, as in the top piece pulled. That's what started the chain of events that the discussion here has focused on.

This is my opinion. Nothing I have seen in or referenced by this thread is conclusive because there are missing scenarios.

This was discovered in the 1980's.

Opinions vary from useless to potentially invaluable. The reasons for that are as varied as the multitude of factors involved in trad climbing protection failure, which limits the ability to reasonably test and accurately identify the technical "failure modes". Meaningful and truly useful accident analysis is opinion, and therefore conjecture. Not everything can be scientifically and/or statistically ascertained. I suggest the root cause of this accident is the top piece blowing. Discussion should start there. I suggest starting a new thread on trad protection failure. Thanks for your post Leif. |

|

|

Ok, this one IS a snarky rebuttal: Dow, your argument is akin to stating that every individual in a community must make the same mistakes and that learning from others is not possible. For background, I work in an industry that intersects aviation and medicine. In both of these industries, human error is the largest source of accidents. In spite of that, aviation has used root cause analysis of accidents to become safer by orders of magnitude over the last century. Despite recent headlines it remains safer than driving your car. Now go look up the number of annual deaths due to medical mistakes. It's estimated to be 250k in the US alone!!!! The medical field has been slow to adapt root cause analysis of errors and it shows in the numbers. Clearly we can learn from the decisions of individuals. Back to the incident at hand. Nobody is arguing that BD made defective gear. Rather, we are analyzing the decisions of the individuals involved so that we can make different decisions in the future. See my last post for a summary of the identified risks and potential corrective actions. Have I convinced you yet that thoughtful analysis improves safety, or are you going to continue telling accident victims to look in a mirror while pretending you're incapable of making a human error? |

|

|

Eric Craig wrote: Other than the falling off part, protection failure is the root cause, as in the top piece pulled. That's what started the chain of events that the discussion here has focused on. I agree the failure of the top piece of gear was a major factor in the accident, perhaps the primary one, but I think there is a good reason the discussion has focused on the other parts of the accident. Everyone knows (or should know) the importance of placing good gear, and there is already a ton of information out there about how to do that. It’s much less well known and less obvious how multiple pieces can unclip in an accident like this. Even when I have good gear I trust, I still aim to achieve redundancy and want my lower pieces to catch me if the top piece somehow pulls when I’m high off the ground. This accident certainly reinforces the importance of making good placements, but it also shows that placement quality alone doesn’t ensure redundancy. If the lower carabiners didn’t unclip/break, this accident would probably have been far less severe. It’s served as a useful reminder for me to keep a couple extra carabiners or lockers easily accessible so I have the option to increase the effective redundancy before any cruxes where I might fall or on sections with marginal gear. I used to treat this as so rare that it was hardly worth considering, but these accidents have caused me to reassess that. |

|

|

A failure mode that I don't see mentioned so far is "double clipping" during the fall (maybe there's another term?) |

|

|

I agree completely that the subject of chaotic rope behavior is worthy of discussion. I was aware of some aspects of this prior to 1990, when I was receiving technical bulletins from Edelrid. The studies conducted at the time lead to new UIAA parameters for carabiner design. This preceeds the development of EN standards. Apparently, there has been a resurgence in these type of carabiner/rope security incidents. I wonder why? Then there is the question of what is more prevalent, simple failure of one or more placements, or a series of failures, some of them involving the rope coming unclipped due to chaotic rope behavior? Another question is: what type of trad placement fails (pulls) most frequently under the strain of a leader fall? One thing appears to be fairly clear, incidents of this type are becoming less rare. Again, WHY? So there is a ton of information out there on making good placements, but apparently either not enough, or not good enough information. Edit: Austin, that's a new one on me. And you say it has actually happened to you? That's what I read, not really questioning you, kinda want to be sure. |

|

|

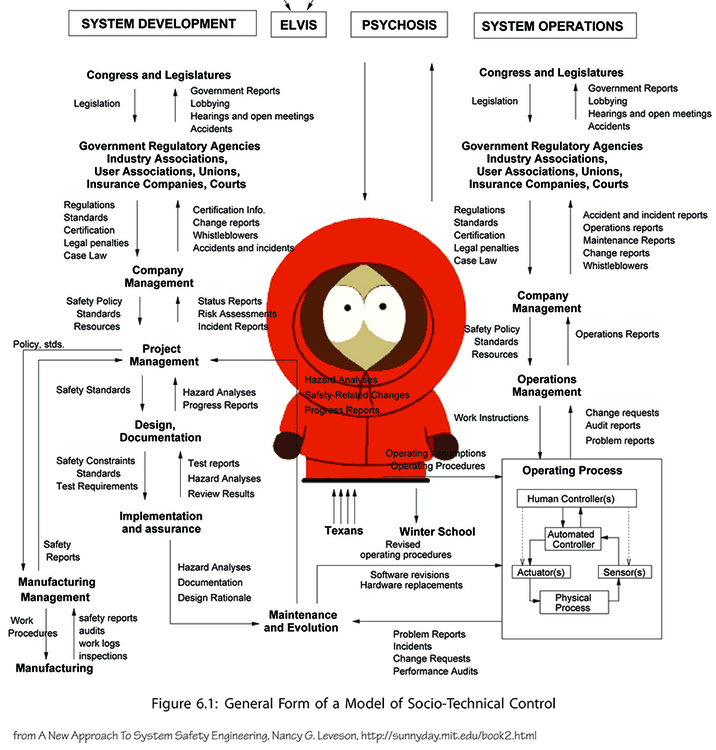

TLDR In my opinion, it’s a systems problem. Thus, blaming any individual component—the victim, the rope, the carabiner, the belay, the cam—is A fine way to look at things, but probably insufficient in and of itself. I attach an image that might suggest a range of perspectives from which to look at risk management. My opinion is guided by N Levison’s system safety work and JM Stewart’s work on creating viable risk management community in organizations. As noted above, there are organizations and industries that have gotten beyond blaming the victim and improved risk management by orders of magnitude. From the perspective of the rope snapback?/zipper failure mode—where one anchor fails, precipitating unusual failure of more below—my GUESS is that this sort of accident happens about as often as ropes are cut or compromised by acid contamination, a few dozen times in the last few decades. There are lots of other things that contribute to climber demise orders of magnitude more frequently than the snapback of rope in the event of gear failure during fall arrest. Climbers can be reasonably confident that gear works, that if the top piece fails—because the top gear is tiny & hurriedly placed, the crack slippery, the rock less than sound—the backstop piece will work. That such confidence is unwarranted in one in ten millions events is perhaps why this RRG accident and the several other unusual snapback?/zipper events are troubling to climber psyche. To add to Eric’s “old technical info” observation: I know that the UIAA moved the open gate strength from 6 kN to 7 kN at about the time Eric was getting the Edelrid technical bulletins. The number of carabiner failures went down noticeably shortly thereafter; but not to zero. And I think I know that in the 80s the ocean engineering world was concerned about ropes snapping due to tensile failure—because tethered oil platforms and cutting anyone standing nearby in half. The Italian Alpine Club has for a long time recognized that fall arrest has a normal category and a this-is-a-big/hard fall where weird things happen category. Much of this has been communicated to me orally, so I can’t provide a publication. More recently (2015 +/-?), the UIAA Safety Commission looked into alternative axis loading of carabiners. It’s clear to many that carabiners hang up in funny ways, especially when clipping bolts. And I’m guessing that trad climbers are familiar with looking down and seeing a carabiner hanging from an alpine draw in a way that would prevent the loading from being along the spine. The challenge from a standard point of view is being able to reproduce the alternative axes that should be tested, so there is no alternative axis test. But carabiners clearly hang up in funny configurations that don’t lend themselves to high fall arrest forces. Caveat climber. I’m curious to know whether there is in fact an increase in the total number or rate of such snapback/zipper incidents. Is it just because there are 1000 x more climbers now than there were in 1985 and now they all post all their heinous fall videos on the internet? Maybe the data exists and just needs to be gleaned. I’d be curious to know the age/use of the rope in this incident. It is well known that ropes stiffen with use, and I’ve often wondered whether increased forces due to such stiffening contribute to gear failure. If someone has the carabiner parts, a little forensic investigation would show how they failed. The carabiner manufacturer could tell you open gate, nose hook, closed gate, alternative axis… If you need somewhere to send the parts, forward them on to Pete Takeda at the AAC. As a shameless plug, my understanding of carabiner failure is enshrined in a youtube video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-mwgbcffOrg&t=2s

|

|

|

Eric Craig wrote: I have the rope clip itself into a lower piece around 1x/year. Never with the top piece failing, but I would guess that has happened to someone before. |

|

|

Eric Craig wrote: Increased prevalence or merely increased reporting/awareness? Making your assertions is impossible without knowing a baseline and without knowing numbers over time. |

|

|

Austin Donisan wrote: What? In the 50+ years me and my partners have been climbing this has never happened to us. What the hell are you doing? |

|

|

Marc801 C wrote: If there is evidence to the contrary of my "assertions", please provide it. RE old technical information: the phenomenon of carabiner gate flutter during leader falls was brought to my attention by the one of the aforementioned Edelrid Technical bulletins. Who actually conducted the experiments showing this I don't recall. Not only did this lead to higher gate open strength standards, but also greater spring pressure on the gates. I believe the testing and resulting new standards came about because of failures in the "new" lightweight carabiners that appeared during the 1980's. I recall the reporting from the tests also showed that standard weight (2.1 - 2.4 or so ounce) were less prone to gate flutter than the new lightweights (1.5 oz +/-). It was considered to be a simple matter of inertia. These recollections and their being similar to the primary subject of this thread, and the long period of quiet on the subject, are what lead to my "assertion " that the issue of lead rope to carabiner security is on the rise. OF COURSE I could be wrong. But if I am not wrong, then what? Just blindly follow seriously limited data, or just do what is fashionable? Like you Marc801 C, I have never had a carabiner unclip during a lead. I also have never had a piece of pro fail to hold a fall, but I think a time or two a leader I was belaying did. Still never saw any of the gear come unclipped. So by that definition, I guess I am not an expert. |

|

|

Are you sure about this? Gate flutter is usually brought up as an argument in favor of wire gate carabiners. The lower inertia of the gates mitigating flutter. Wire gates tend to be lighter, not heavier. |

|

|

Austin Donisan wrote: Austin could you explain a bit more how this situation happens? Does it happen in a fall or while hanging on the rope (or both)? Do the pieces need to be close together? Is it only possible when all the gear is in a perfectly straight line? I ask because I've experienced a few instances of pieces mysteriously unclipping that I haven't been able to explain (didn't see it, just looked down to see a dangling carabiner) and I'm curious if this is a possible cause. |

|

|

Alex R wrote: The technical information I refer to predates wire gate carabiners. Failures of the early lightweight carabiners are what precipitated the testing I refer to. I believe that the rope coming unclipped was not part of the equation, but carabiner gate flutter was found to be the the likely culprit of breakage, by creating a leader fall load on an open gate. The result was creating or raising (as indicated in an upthread post) gate open strength and stronger gate springs. It was noted that during the testing that standard weight carabiners (which typically weighed 2.1 - 2.4 ounces at the time) were less susceptible to carabiner gate flutter than the new lightweights (1.6 +/- oz.). These new lightweight carabiners were manufactured in Europe, smaller in size, of smaller stock, and the asymmetrical D shape that is nearly universal today. But based on the feel of the gate action, I believe most all European carabiners henceforth had stiffer gate actions. Chouinard and SMC and maybe Omega gate springs/action did not change. Those manufacturers didn't seek UIAA certification. I think the British manufacturers also initially kept softer gate actions as well. Everything is different now. You could very well be correct about wire gates. Regardless of whether it is just opinion, or opinion supported by test results. I no longer have possession of the information I quote. I collected a lot of it in preparation for compiling the first AMGA Rock Climbing Guides Manual. Both the computer and email address I used are long gone, and most of the technical information didn't go in the manual. We focused on GUIDING. |

|

|

Just some anecdotal observations - there's a lot more people climbing trad in general, and particular whipping on trad gear. I've always been a bit leery to fall on trad, as many of the routes I have done have had consequential fall zones or otherwise (i.e. self decided) lack of protection. However, I have noticed a lot of people taking a lot more falls even on easier routes at areas like Twall. Gym culture? idk, just what I'm seeing. Also, I've climbed in a lot of areas and I feel like the RRG is among one of the sketchier places to climb trad. Many of the placements are not in super solid rock like you get at the New, around Chattanooga or granite out west. A lot of the trad feels (and is) sandy or dusty, especially as you move from the uber classics that everyone does.Perhaps both of these factors played into the accident, from which in my limited understanding, the climber was very lucky to virtually "walk away" from. |

|

|

I've been reading this thread with interest. I do think it has been an interesting and productive discussion. We all know there are plenty of locations on routes that are "do not fall" spots. The crux on this route, from the description, does not seem to be one of those routes. However, with an 11d crux protected by a 00 Mastercam, one might anticipate that there are some reasonable odds that the crux piece might fail with a fall, and that the underneath pieces are critical backups. It's really bad luck and not at all predictable that the events would have unfolded as they did. This thread has been productive in summarizing things people do the reduce those odds of rare failure, like using a slider lock draw (I love mine) or paying attention to dogbone vs flexible draw to change the forces on the gear with a fall. This is why I found Austin's photo interesting. Theoretically, I can see what he's getting at, and I had never thought about that scenario. I have a habit of placing double pieces close to each other at that place on a crack route that I call the "hit the ground spot". If I can (and I usually can), I set the draws on these pieces so that the bottom biners are at the same level. Are they "equalized", not technically, but this seems better to me than just having them stacked close to each other. I'll often do this "double up" technique high up on a route if it looks like I'm coming to a long stretch of runout. But for me, all this is for routes, which, while they may be runout and with small gear, are fairly easy, and it's not burning huge amounts of energy to place the gear the way I want it. At the end of the day, the "root cause" of climbing injuries after falling, is that falls are never guaranteed to be safe. This was some very bad luck, I hope the climber recovers completely and quickly from the injuries. |

Continue with onX Maps

Continue with onX Maps Sign in with Facebook

Sign in with Facebook