|

|

jktinst

·

Oct 5, 2014

·

Unknown Hometown

· Joined Apr 2012

· Points: 55

I've been trying for a while to find information on how to deal with suspension trauma in the context of a leader dangling unconscious after a fall. The article "Risks and management of prolonged suspension in an alpine harness" by Roger Mortimer, found on the itrs-online.org site, has given me the best pointers yet to a particular course of action even though its practical recommendations are directed more specifically at cavers. References to any other useful material looking at implications for climbing self-rescue would be greatly appreciated.

WIDELY DIVERGENT APPROACHES TO DEALING WITH LEADER DANGLING UNCONSCIOUS

In this situation, there is no question that the ideal scenario is if the belayer can lower the victim back to the ground or the belay ledge with minimal danger to himself or risk of aggravating the existing injuries of the victim (or causing additional ones). However, when it comes to dealing with less favourable conditions and in a situation where outside help cannot get there very quickly, a number of very different approaches have been discussed in manuals and various forum threads of which this was just the more recent.

mountainproject.com/v/self-…

One procedure often recommended is to escape the belay and ascend to the victim as fast as possible, establish/reinforce an intermediate anchor, secure the victim to this anchor via a loose load-releasable tether, do an initial assessment, provide what first aid must/can be provided on the spot, then downclimb/prusik back to the belay and release the rope (loading the tether with the victim in the process), climb/prusik back up, tether the rescuer to the intermediate anchor as well, recover the rope and do one or more tandem rappel(s) to reach a ledge and desuspend the victim.

This procedure can take a long time and, given the dangers of suspension trauma, some say that the belayer should instead rapidly lower the victim no matter the risks. In this scenario, if reaching the end of the rope before the lowering is completed, the belayer should tie the rope off at the ATC, unclip from the belay anchor and continue lowering the victim by counterbalanced (CB) climbing, despite the risk of potentially finding himself high up on the pitch with very few pros of unknown solidity still clipped on the rope.

INTERPRETATION OF ARTICLE BY ROGER MORTIMER

The main points I extracted from the article are:

- The first symptoms of the suspension syndrome can start appearing very quickly (in a few minutes) but there appears to be a lot of variability in different people's responses to suspension trauma. Nevertheless, the consequences of a relatively short time (15, 20, 30 min.?) of unconscious suspension seem to be usually fairly mild (lots of caveats there, as well as a few clear exceptions). Of course, these consequences can rapidly escalate to much worse outcomes with longer suspension times.

- While lowering as quickly as possible to the nearest flat surface remains the priority, it appears to be possible to reverse or significantly alleviate suspension trauma while remaining in suspension by raising the victim's legs above his body.

The first point places the urgency squarely at what I would consider to be "the limit"; ie not quite so urgent that I would consider it justified to do the CB lowering/climbing when there are significant risks for the victim and the rescuer; but much too urgent for it to be realistic to escape the belay, ascend to the victim and bring him back down to a flat surface, even in the best of circumstances.

I've felt for a while that the possibility (or not) of relieving the trauma while remaining in suspension would probably be a deciding factor in selecting an appropriate approach. I take from the second point of the article that the rescuer should indeed be able to improve the victim's prospects and buy himself more time in which to complete the lowering by taking the time, after performing a rapid initial assessment, to rig various slings to support him in a safer position, provided his injuries allow it.

POSSIBLE POSITIONS TO RELIEVE SUSPENSION TRAUMA?

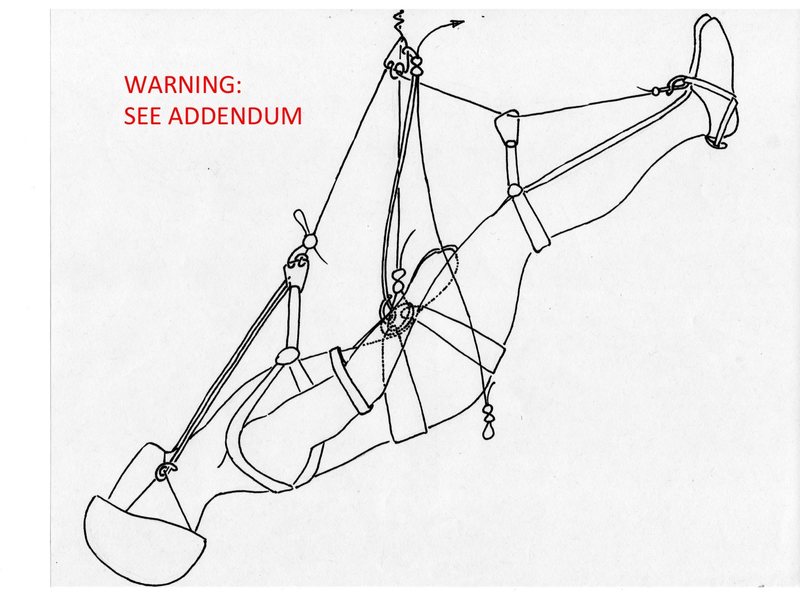

Among the various possible positions, the two shown here seemed to be the more promising ones. Achieving the first position quickly, safely and with the kind of gear typically found on a trad rack is pretty straightforward for the feet, knees and torso but the head is a whole other kettle of fish. The best way I found to deal with the head was to forget about using standard gear and sew a dedicated helmet/head suspension sling, as shown. With this system, the entire rigging procedure with both myself and my test “victim” in suspension against a climbing wall takes about 11-12 min, which is longer than I had hoped but not as bad as I feared. Repeated training could probably shorten this to 9-10 min but that would not be representative of what could be achieved in a real emergency.

I've tried to illustrate the different aspects of the system as clearly as possible. I realize that the illustration of the head/helmet suspension sling cannot clearly show how it's made. If anyone would actually wish to have more detailed explanations and photos of this, I'd be happy to provide them privately. One other aspect that could probably use a bit more explanation is the cord system surrounding the "main bight". This is simply a length of 7mm cord folded in an "N" shape. The top part of the N is knotted, creating a) a long bight out of the bottom "point" of the N, which is girth-hitched to the victim's harness, and b) a small "main bight" out of the top "point", which can be clipped to the main suspension biner (and, later, during the tandem rappel, to the rappel brake biner). The "top loose end" emerging from the knot is used to secure the victim to the intermediate anchor (and any other rappel anchor if additional tandem rappels are undertaken) with a load-releasable hitch. The "bottom loose end" can be adjusted and knotted to serve as tether for the rescuer in the tandem rappel.

CAUTION: SEE ADDENDUM BELOW

SuspTrauma001

I considered alternatives to the dedicated sling that could achieve the same position but all took longer than the sling (some a lot) and resulted in significantly more jostling of the head and neck (some a lot more jostling); again: more details are available on demand if anyone really wants them. A "realistic" alternative to the head/helmet sling would be if helmet manufacturers would all start adding little webbing guiding slots to the upper sections of their helmet straps that would allow a head-support sling to be threaded through them easily and that would keep this sling positioned correctly as shown, preventing it from sliding lower down along the strap and letting the head drop back and down. However, I don't seriously expect to ever see this helmet mod happen. This particular self-rescue issue is just too far off anyone's radar. In addition, while, at first glance, it appears to be a very small mod that could be easily applied to all helmets, it may have implications for the load-bearing capabilities of the straps and their attachment points to the helmets that could make it somewhat more complex to implement.

The main advantage of the second position is that it can be implemented using only standard climbing gear. Tilting the whole body at an angle not only brings the feet up but also places the body at such an angle that the head dangling down will not result in too much hyperextension of the neck. A snug torso sling is used with the first position but would be even more critical here to make sure that the victim could not slide out of his harness. Slings can be girth-hitched to the lowest part of the helmet's straps as shown. These would support and stabilize the head somewhat (though not nearly so well as the first position). Of course, the neck would also still be somewhat hyperextended.

CAUTION: SEE ADDENDUM BELOW

SuspTrauma002

My preference (especially now that I've made the head/helmet suspension sling) is for the first position. I feel that it would be more comfortable for the victim but also more compact for the rappels and easier to manipulate through subsequent weight transfers and rappels. Ideally, the victim would be deposited on the first ledge reached to be able to perform further assessments and first aid. The first position would make this depositing easier. If the rescuer decides to undertake further tandem rappels with the victim still incapacitated, this position is also potentially more amenable to leaving the victim suspended by the load-releasable hitch and "main bight" + suspension biner during subsequent rappel anchor set-ups, either because no suitable ledge is available at that point or to save time by avoiding depositing the victim and having to haul him up again to get him back on the tandem rappel.

Having said all this, I really don’t know whether either position is anything like what Roger Mortimer might have had in mind and whether they would really provide sufficient relief from suspension trauma to justify the initial time investment, to complete the first tandem rappel, undertake further rappels, forgo desuspending the victim during those, etc. I tried contacting Dr. Mortimer directly without success so I'd really appreciate comments from the medical and vertical rescue communities.

ADDENDUM1: THESE POSITIONS HAVE BEEN CALLED INTO QUESTION IN THE DISCUSSION BELOW. THE MAIN OBJECTIONS RAISED CONCERNED THE POSITIONS THEMSELVES. HEAD TRAUMA IS PRESENT (BY DEFINITION IN THE CASE OF A LEADER UNCONSCIOUS AFTER A FALL) AND BOTH POSITIONS WOULD AGGRAVATE IT. ALSO THERE IS THE RISK OF THE TONGUE OBSTRUCTING THE AIRWAY. FINALLY, IF SIGNIFICANT BLOOD LOSS HAS OCCURRED, LOWERING THE FEET AFTER KEEPING THEM ELEVATED MAY LEAD TO A POTENTIALLY DEADLY DROP IN BLOOD PRESSURE. FOR EMS & EMERGENCY HOSPICAL CARE, THE MORE GENERALLY ACCEPTED POSITION IS THE SEMI-FOWLER, WHICH IS JUST AS EASILY ACHIEVABLE IN SUSPENSION AS POSITION1 USING THE SAME RIGGING. HOWEVER, THE CRITICAL QUESTION REMAINS: IS ANY POSITION LIKELY TO HALT OR REVERSE THE PROGRESS OF THE SUSPENSION TRAUMA (IE, IS IT WORTHWHILE TO INVEST THE TIME TO ACHIEVE ANY POSITION WHILE REMAINING IN SUSPENSION)?

REMAINDER OF THE RESCUE: SHORT HAUL OF THE VICTIM TO FREE THE TOP END OF THE ROPE

Another way to save a lot of time in the overall procedure is to make sure, before escaping the belay, that the victim is left positioned about 2m below what appears to be a good location to build an intermediate anchor. This should bring him a the right height to tether to this anchor after the short haul. Given the urgency, I would consider it justified to lower the victim (hopefully just a short distance) to that position before escaping the belay, even though the potential risks of doing this are unknown at this point. Even taking this precaution, escaping the belay, ascending to the victim, building the intermediate anchor and placing the victim in reclined suspension in under 20 min is still quite a challenge but not nearly as much, I feel, as aiming to have rappelled down to a ledge with the victim. While on the topic of things that can be done to save time, converting the main belay anchor to an upward pull anchor can use up a lot of precious time so if one upward pull pro is already in place as part of the main anchor or if at least, some thought has been given ahead of time to how some of the downward pros could be quickly reconfigured to upward pull ones, it would be save a lot of valuable time in an emergency.

Now about the remainder of the rescue strategy: a faster option than the "additional trip down and back up the rope" to release the rope is to effect a short haul of the victim to free up enough slack on the rope to be able to transfer him to the load-releasable hitch, undo his harness knot and recover the rope from the pros above. After building the intermediate anchor and placing the victim in a better suspended position, the rescuer should have another look at the top fall-catching pro. If it looks somewhat dubious, the rescuer could setup and perform a cord haul off of the intermediate anchor. If the victim and rescuer are of similar weight, a 2:1 haul (as shown in the second diagram of the long post on the following page should work ( mountainproject.com/v/self-… ). If the victim is significantly heavier, the block tackle 4:1 haul shown in the 3rd diagram should do the trick.

However, if the top pro looks solid, it will be faster to perform a counterbalanced (CB) haul of the victim from just above him. A simple 1:1 CB haul (with complementary pull-up loop) should do the trick if the victim is not too much heavier than the rescuer. If greater mechanical advantage is needed, my preference, based on the various systems I tested, would be the Spanish Burton 3:1 complemented by a pull-up loop, as shown in the 4th diagram (achieving an effective haul ratio of well over 2:1).

Of course, even faster would be to cut the rope just above the victim's knot to instantly transfer him to the releasable hitch and free the rope. If this option is preferred from the beginning, ideally, the victim would be left only about 1m below the prospective intermediate anchor point before escaping the belay, not 2m as mentioned above. However, with this approach, it would be difficult to avoid jostling the victim. In addition, the CB haul can be performed very quickly (even if it requires a higher mechanical advantage) and it takes place after the victim has been placed in a better suspended position (ie, presumably once the urgency has lost a bit of its edge). As a result, the short time saved by cutting would be, in my opinion, of too little consequence to justify the loss of even a short section of rope and the hassle of dealing with a fraying end of the rope. Of course, the knot may be too tight to undo after the fall (especially if there are other complicating factors, like rain, cold, etc.), making cutting the only reasonable option.

ASSEMBLING A MAKESHIFT TAGLINE TO ACCELERATE RAPPELLING WITH A SINGLE ROPE

Different options may be considered for setting up the tandem rappel. Of course, if using double ropes or if a proper tagline is available, a regular double-rope or tagline tandem rappel can be set up from anywhere on the pitch. If using a single rope and no tagline, the rescuer could still consider the possibility that a makeshift tagline could be assembled with lengths of cord and webbing available on the rescuer's and victim's racks to extend the free end of the rope. Doing this could greatly speed up the remainder of the rescue procedure, especially if further rappels may be needed. After escaping the belay, the rescuer could ascend the rope trailing the free end of the rope to be used as the "bottom half" of the tagline. When coming to the end of it, he would leave it secured to the wall, a pro or the rope before continuing ascending to the victim. After having attended the victim and placed him in a reclined/suspended position, he would take a couple of minutes to knot together additional cordage to assemble a "top half" of the tagline long enough to reach and be joined with the bottom half. He will then do this joining on the way back down with the tandem rappel.

If the rescuer does not use any of the various methods for recovering the rope quickly and he attaches one end of the single rope to the intermediate anchor in order to be able to bring the victim all the way back to the main belay with a single one-strand tandem rappel, he may need to reascend to recover the rope for further rappels. However, this rope recovery return trip will at least be done after, not before, the victim has been desuspended, reassessed, provided with additional first aid and stabilized as well as possible

Final note of caution: if considering tandem rappelling on a single rope with a regular rappel device, be sure to know how to increase the friction on the braking strand to maintain sufficient control.

|

|

|

kenr

·

Oct 6, 2014

·

Unknown Hometown

· Joined Oct 2010

· Points: 16,608

Thanks for taking the trouble to do the analysis.

You might find some more ideas in instructional texts and accident stories about rescue from falling into crevasses on glaciers -- where an injured (or non-injured) Faller sometimes hangs (or is wedged in an upright position) for long periods of time.

Crevasse rescue strategies sometimes have an additional time delay problem: It's just cold if the Faller is wedged into ice/snow on two sides (and was dressed lightly for uphill travel when the fall happened).

Ken

P.S. My reaction is that rescue on a wall (or in crevasse) with a party of two can get real tricky for reasons most of us don't think of in advance. And then there is the next problem of how to evacuate an injured climber even after you get them off the wall - without a motor-powered support team. (My personal response to that is to carry a SPOT satellite rescue beacon).

P.P.S. I think there was a story in the last year or so about someone skiing on Mont Blanc who punched through down into a crevasse and got wedged. A very sophisticated and experienced rescue team soon arrived by helicopter. Though conscious and not seriously injured, he was so badly wedged that it took hours to extricate him from the ice.

Too many hours. He had already died.

|

|

|

jktinst

·

Oct 7, 2014

·

Unknown Hometown

· Joined Apr 2012

· Points: 55

In crevasse rescue, if the victim is not able to ascend back up on his own, the only option is hauling. There often is more than one person pulling on the haul system and, in anticipation of the need for crevasse rescue, the team often carries specialized gear (pulleys, ascenders, microtraxion, etc.). Also, the space in which to spread out the haul system is much less limited than in typical rock climbing self-rescue situations. As a result, there is a wide range of hauling systems that can work well for crevasse rescue and that are likely well-known and regularly practiced by the team. All this, combined with the fact that the height of the fall is generally not too great mean that these hauling systems can typically be implemented very quickly, which, in turn, means that suspension trauma is of much less concern, even in those very rare circumstances where the victim remains unconscious for the duration of the rescue.

In rock climbing self-rescue, lowering and tandem or counterbalanced rappelling are much better solutions in general and in particular for the situation of the leader dangling unconscious after a fall. I don’t recall anything specific to suspension trauma in crevasse rescue situations from either Tyson&Loomis, Fasulo, Freedom of the Hills, accident reports, internet searches or the pretty comprehensive literature review carried out by Mortimer in his article. Accident reports and strategies to deal with the issue most often come from the fields of caving and canyoneering (or work site safety) and the methods recommended are usually specific to rescuing rappellers, often with extra people and ropes available (releasable attachment of rappel ropes to the anchors with extra rope available at the top for lowering or hauling, pick-off techniques, etc.). I would certainly be interested in any specific reference to suspension trauma in the context of crevasse rescue.

Mortimer’s article makes it abundantly clear that people can have a very wide range of responses to suspension trauma, from some who died very quickly and for no other reason that the autopsy could find, to others who walked away from a long period of unconscious suspension with little to no consequences. As a result, every case has to be treated as extremely urgent. Calling for outside help by any means available should indeed be considered as the first critical step of the (self-)rescue but it is essential that the belayer-turned-rescuer also be able to quickly undertake an action plan that has the best possible chance of a) reversing, stopping or at least slowing down the trauma’s progress, and b) getting the victim desuspended (ie lying down on a ledge or the ground) as quickly as possible without waiting for outside help and, as much as possible, without causing additional injury to the victim or resulting in a dangerous situation for the victim and the rescuer.

|

|

|

kenr

·

Oct 7, 2014

·

Unknown Hometown

· Joined Oct 2010

· Points: 16,608

jktinst wrote:

> In crevasse rescue ...

> ... hauling systems can typically be implemented very quickly

Except when it's a party of two - (true for many ski tours and alpine climbs nowadays).

Except when the victim gets wedged - which seems to happen a fair amount in ski mountaineering around Mont Blanc. Which is why the Chamonix rescuers have suggested special instructions about equipment for skiers - to make the rescuer's job much quicker.

Ken

|

|

|

jktinst

·

Oct 8, 2014

·

Unknown Hometown

· Joined Apr 2012

· Points: 55

You're right. I was looking for reasons why I hadn't come across anything related to crevasse rescue when I should have realized instead that I never actually searched for suspension trauma + crevasse rescue key words. Searching for variations on this turned up one reference on that specific topic ( mountainz.co.nz/content/art… ). However, it seems outdated, based on the post-desuspension treatment recommended, ie, he recommends a sitting up position whereas the Mortimer and the British Health and Safety Executive articles specifically debunk this and recommend lying the victim down.

Regarding the options for suspended positioning, he mentions keeping the knees of the victim lifted up by working the leg loops lower down the legs. Have you seen other recommendations elsewhere? The Mortimer and British HSE review articles simply recommend elevating the legs without clearly specifying how (re-reading these made me realize that I'm the one who added "above the body". The original articles don't actually say that).

However, in practice, if you start with an unconscious victim dangling in a sit harness, if you want to elevate the legs by the knees only and without flipping the victim upside down, you have to add a chest sling first. Clipping this to the rope (and the N-folded weight transfer cord) to maintain a somewhat upright position, you end up with a very awkward-looking position that is basically like an upright foetal position with head tilted way back and arms dangling down and to the sides. The main reason I really don't like this is that I feel (but don't know for sure) that this position, while faster to implement, would be less effective at providing relief from suspension trauma than the two I tested. I also dislike it for other reasons, like the comfort and safety of the victim (floppy head and arms, discomfort of lower legs dangling down from an under-the-knee strop) and the difficulties with subsequent manipulations.

|

|

|

Thomas Willis

·

Oct 8, 2014

·

Unknown Hometown

· Joined Nov 2010

· Points: 0

I would think that unless the helmet sling is adjusted exactly right that it would be very easy to cause the neck to flex causing airway obstruction in an unconscious victim. Have you tried this in practice - is it easy to keep the neck in a neutral position?

|

|

|

jktinst

·

Oct 9, 2014

·

Unknown Hometown

· Joined Apr 2012

· Points: 55

Edited to add the PS

The head/helmet suspension sling is made to just slide easily over the helmet (ie without having to pull hard or jostle the head), getting the straps holding the back of the head into the correct place in the process. After that, all adjustments for the height of the test victim (distance between head and chest) and the position of the secondary head-torso suspension biner (to hold them aligned with each other while in suspension) are done with the daisy chain part of the sling.

I’ve tested the 1st position with the head/helmet sling three times: once with a "test victim" shorter and lighter than me, and twice with one about the same size as me. I felt that the daisy chain provided solid and easy to adjust attachment points that worked well for both.

Two climbing partners who haven't practiced the suspension drill with each other before could just take a minute to try the sling on the ground to find out which loop settings they would each most likely require. Then if, using those settings, the (test-)rescuer realizes that it makes the system hold the head a bit too far forward, he can simply move the secondary head-torso suspension biner to a lower loop along the daisy chain and this will bring up the torso and lower the head slightly.

For the 2nd position, the neck ends up hyperextended anyway. The sling adds a bit of stability but cannot hold up the head. To keep things simple(r), I didn't show details of how to adjust that sling but some adjustment would definitely be needed (shortening to the correct length) to tug at the head without pulling hard on it.

PS I just realized that there is a small mistake with the first drawing: the position of the main suspension biner should be a little bit higher. Not much, a couple of inches at most but it makes a big difference. Set too low and it allows the knees to buckle and the feet to drop down. This is not a huge deal but it kinda defeats the purpose of going to the trouble of linking the feet into the suspension system. Basically, the distance from the main suspension biner to the victim is a compromise: low enough to keep the system compact and easier to manipulate, high enough that it keeps the legs in the optimal position.

|

|

|

jktinst

·

Oct 20, 2014

·

Unknown Hometown

· Joined Apr 2012

· Points: 55

I posted about this on the French camptocamp forum as well. It seems that the prevalent attitude over there among the people who participated in this discussion and an earlier one on suspension trauma is heavily influenced by a review article written by a Dr Querellou. The highlights of the article most relevant to climbing are:

- death can occur after 5 min of unconscious suspension and, beyond 15min, 50% of victims will be dead (!!?!). While this paper references many of the same primary studies as Mortimer’s paper, this particular gem does not come with a reference and I really can’t figure out how (s)he (no first name given) got these stats.

- For the necessary self-rescue before SAR arrives, it is recommended to place the victim in the fetal position before lowering and desuspending (but, as usual, no information is given as to whether this merely slows down the syndrome's development or if it might be significantly more beneficial than this).

The replies mostly hinge on the first statement (of course, since it is so dire) and conclude that the only option in a climbing situation is to lower the victim immediately and rapidly to the nearest flat surface, by counterbalanced climbing if necessary, regardless of what injury he might have (known or unknown), or what additional injuries this might cause him. I figure that with this scenario, there really isn't much point in the rescuer bothering to place the victim in the fetal position when they cross paths. By then the victim has already completed most of the lowering unassessed and unattended. The rescuer should do a quick assessment at that point and perform whatever urgent first aid action could not wait until after the lowering has been completed and the rescuer has rappelled back down. However, taking the time after this to place & attach a chest harness and a sling under the knees of the victim when he's probably no more than a minute or two from desuspension seems pretty pointless.

The best compromise I can think of that includes lowering as fast as possible, some mitigation of risk for both the victim and the rescuer, and placing the victim in the fetal position for most of the lowering is the following.

- Lower the victim past a few of his last pros; then escape the belay directly to a counterbalanced rope ascension rig and ascend the rope.

- Partway up, build a solid anchor to hopefully stop further ripping of pros should the top fall-catching pro blow and start a chain reaction.

- After reaching the victim, do a cursory assessment, provide the most urgent first aid, place & attach a chest harness, and place & attach a sling under the knees.

- Counterbalance rappel with the victim to the anchor, detach the rope, reclip it as a runner and continue rappelling.

- After reaching the end of the rope, lock it off at the rappelling device and start counterbalanced climbing until he is finally deposited.

Even if you’re familiar with the techniques involved and are fast (and lucky) with building the back-up anchor, I can’t see how desuspension could happen in less than 30-35 min and the risk is still quite high. Any additional precaution to reduce that risk will just add more time. This apparent contradiction between the two highlights from Querellou’s article got me wondering if the second one might not be directed solely at cavers and workers in vertical environments. In these situations, it is likely that a rescuer will be able to quickly reach the victim by rappelling on another rope and transfer him to the rescuer’s harness or rappel device with the help of other partners above (who could detach or cut the first rope). If that is indeed the most relevant context for the recommendations, it would also mean that the second one does not at all imply that adopting the fetal position would effect a significant relief of the syndrome. In this context, even a slight slowing down of its progress would justify the very short time investment of simply lifting the knees (since a chest harness is most likely already in place).

Having started thinking along those lines, I realized that the same could in fact be true of Mortimer’s and the HSE’s recommendations to raise the victim’s legs before desuspending. I attempted again to contact Mortimer to clarify whether that recommendation might indeed have been more specifically directed and cavers and workers, given its time implications for climbers but, again, got no reply. To round off the available information, the self-rescue manuals do emphasize the urgency of desuspending the victim but without providing a time frame of the syndrome's development or clear self-rescue protocols. So basically, all the information I have been able to find is or looks either contradictory, incomplete or both.

Of course, throughout all this, I kept wondering if I'm not making too big a deal out of this, considering how rarely climbers seem to die from suspension trauma. However, I also wonder if, on the contrary, we're not underestimating how often it happens in climbing. The reason why it seems to be better documented for caving incidents might be simply that it is more obvious in these cases where the initial trigger is often exhaustion rather than an accident. Typical caving suspension trauma incidents probably run thus: caver gets exhausted while ascending out, stops moving, then loses consciousness and dies. With such a puzzling death, an autopsy may be done to try and understand what happened. This reveals no obvious cause of death other than suspension trauma.

Now take the equivalent likely scenario for climbing. The leader falls and gets banged up, loses consciousness and dies. If his injuries look like the probable cause of death, do we even do an autopsy? Even if we do, I suspect that it would be rare or difficult to be able to say categorically that the injuries were the sole cause of death or, on the contrary, that they were clearly insufficient to have caused death. Many cases would probably fall in the grey area in between. In short, I wonder if we simply don't know how often suspension trauma might have contributed to a death, accelerating the onset and speed of progression of deadly shock, enhancing its effect, etc. and whether the victim might have survived if a self-rescue procedure appropriate for suspension trauma had been implemented immediately. This is why I keep looking for clearer guidelines and protocols.

If the syndrome cannot be reliably halted or reversed even with an optimal suspended position (ie if it can only be slowed down, at best) and a flat surface for desuspension is fairly easily reachable, then it would be a waste of time to try and put the victim in position one before the initial desuspension. However, doing it might still be useful if it will take a relatively long time to reach the nearest flat surface (2 or more rappels, or roped soloing followed by hauling) or if, after reaching the first flat surface quickly without having used the position, the rescuer must then consider the possibility of further rappels with the unconscious victim. In the latter case, it would not be too unrealistic to achieve the position using only regular climbing gear for the head/helmet & neck. Regarding the second position, Querellou’s article specifically warns against using it for the recovery after desuspension because of the risks of oedema so it's probably best avoided before desuspension as well.

So basically I’m still wondering if anyone might have information or considered comments on the following points:

- What’s the time frame of the syndrome’s development in people who are sensitive to it?

- How much time can be bought by getting the victim into a better position before lowering?

Obviously, it would be silly to expect very clear-cut numbers, recommendations and protocols at this point but some sort of resolution of the many uncertainties and contradictions that are still floating around this topic would give us half a chance to choose an appropriate course of action from among the many options, ranging from fastest-and-riskiest to safest-and-slowest.

|

|

|

Sam Latone

·

Oct 20, 2014

·

Chattanooga, TN

· Joined Dec 2012

· Points: 45

If a persons feet are significantly elevated for longer than 5 minutes, and they have in some way experienced trauma that is causing significant blood loss...when the feet are brought back down the patient's blood pressure will drop dangerously low and could result in death.

This is the reason that trendelenburg position, feet elevated and head dropped, is starting to be discouraged in pre hospital care.

To figure out trauma due to suspension in a harness you should check out medical information regarding compartment syndrome and crush injury.

|

|

|

J. Serpico

·

Oct 21, 2014

·

Saratoga County, NY

· Joined Dec 2009

· Points: 140

Sam Latone wrote:If a persons feet are significantly elevated for longer than 5 minutes, and they have in some way experienced trauma that is causing significant blood loss...when the feet are brought back down the patient's blood pressure will drop dangerously low and could result in death. This is the reason that trendelenburg position, feet elevated and head dropped, is starting to be discouraged in pre hospital care. To figure out trauma due to suspension in a harness you should check out medical information regarding compartment syndrome and crush injury. Isn't that what harness hang syndrome basically is, compartment syndrome?

|

|

|

jktinst

·

Oct 21, 2014

·

Unknown Hometown

· Joined Apr 2012

· Points: 55

Sam Latone wrote:...when the feet are brought back down the patient's blood pressure will drop dangerously low and could result in death. This is the reason that trendelenburg position, feet elevated and head dropped, is starting to be discouraged in pre hospital care... Would you mind clarifying whether you're commenting on both positions or only on position2? Also, if you include position1, please clarify whether you are making a case for not raising the legs above the body in the first place or for keeping them raised even after getting the victim to a ledge or the ground. Finally, it would be helpful to have some indication as to whether your recommendation should be OK for wilderness first aid or if it is more relevant for situations where a rapid intervention by EMS leads to a fast transfer to emergency hospital care. Hopefully, significant blood loss (unless internal) would be picked up in a cursory assessment and dealt with as well as possible, given the circumstances, as part of those “most urgent” first aid actions. However, if dealing with significant blood loss in a wilderness situation, isn't it most critical to keep what blood is still circulating concentrated around the vital organs? In the system shown for position1, the main suspension cord can be easily adjusted to hold the knees and feet in a flatter position if that’s what would be best. This flatter position would be only slightly more awkward to manipulate during the tandem rappelling and weight transfers than the original one. Conversely, the system shown would also allow for the knees and feet to be kept elevated throughout the self-rescue procedure, if needed. Sam Latone wrote:...To figure out trauma due to suspension in a harness you should check out medical information regarding compartment syndrome and crush injury. J. Serpico wrote: Isn't that what harness hang syndrome basically is, compartment syndrome? In his review article, Dr. Roger Mortimer makes a pretty convincing case that suspension trauma is quite different from crush/compartment syndrome.

|

|

|

Bryan Ferguson

·

Oct 22, 2014

·

Unknown Hometown

· Joined Apr 2008

· Points: 635

|

|

|

William Kramer

·

Oct 22, 2014

·

Kemmerer, WY

· Joined Jun 2013

· Points: 935

Just to give myself a little credibility before I comment on your post, I am a full time EMTI and a training officer for my fire department in western Wyoming.

What I have learned over the years of doing my job, is that there is no standard "this is the way its done". Every real life scenario presents with a variety of issues, good or bad. Best anyone can do is do the best they can for the patient with what they have. I like where your thinking was going with the limiting crush/compartment syndrome, and stabilizing the head in your diagrams of rigging the patient, but want to throw some things out there for you to think about as far as patient care.

To start with I want to mention how important airway is, it is the base of every assessment in the medical field, air has to go in and out to live. With that in mind, look at how you have your patient rigged in diagrams. If they are unresponsive, and head is lower than the body, gravity will let their tongue fall back and block the airway. Using airways such as an OPA or NPA will diminish that effect, but would still be a worry.

Along with airway, as someone else previously mentioned, gravity of being in that position will effect your circulation. Should think that if someone is unresponsive from a head trauma, there will be swelling and possibly bleeding in the inter cranial space, thus raising inter cranial pressure (ICP). If patient is inverted, even slightly, gravity increases blood flow to the head, increasing ICP. As ICP increases, it will cut off circulation to the brain, eventually destroying brain cells. This happens much quicker than crush or compartment syndrome.

On to crush and compartment syndrome. Yes, it can happen fast. Or it can take forever before it occurs. Just depends. It does kill. In this case it will kill if the patient has been hanging there, developed it in their legs, and climber lowered or whatever was done to take pressure off of leg loops on harness too quickly. What happens is that the tissue cells in the legs are starved of oxygen, becoming acidotic, turning the blood cells acidotic as well, and when the pressure is released and those acidotic blood cells return to the heart they turn the heart acidotic and will put the patient into cardiac arrest. The best way for crush and compartment syndrome of this type to be handled in the field is for the pressure to be very slowly released as the patient is administered Sodium Bicarbonate by IV. Most ambulance services carry this med on their rigs. So yes, it is important to keep the patient from getting it, but more important to recognize if they already have it.

Also should maybe think about how you have patient rigged in diagrams. Having dealt with many unresponsive people, their extremities and head always flop in crazy ways, no matter how well you hold or secure them. Personally I would think rigging them to come down feet first, almost vertical. This would let their feet hit stuff on the way down instead of their back and head, which is already injured. Would also be easier to maintain an airway. Yes, it won't help with compartment and crush syndrome, but plan it out, go down to a spot where you can rest them for a bit before doing it again.

As I said, there is no real right or wrong here, just do the best you can with what you have, and sometimes the best thing to do is take a mental step back, a big breath, and some different idea might present itself that will work better.

|

|

|

Sam Latone

·

Oct 22, 2014

·

Chattanooga, TN

· Joined Dec 2012

· Points: 45

jktinst wrote: Would you mind clarifying whether you're commenting on both positions or only on position2? Also, if you include position1, please clarify whether you are making a case for not raising the legs above the body in the first place or for keeping them raised even after getting the victim to a ledge or the ground. Finally, it would be helpful to have some indication as to whether your recommendation should be OK for wilderness first aid or if it is more relevant for situations where a rapid intervention by EMS leads to a fast transfer to emergency hospital care. Hopefully, significant blood loss (unless internal) would be picked up in a cursory assessment and dealt with as well as possible, given the circumstances, as part of those “most urgent” first aid actions. However, if dealing with significant blood loss in a wilderness situation, isn't it most critical to keep what blood is still circulating concentrated around the vital organs? In the system shown for position1, the main suspension cord can be easily adjusted to hold the knees and feet in a flatter position if that’s what would be best. This flatter position would be only slightly more awkward to manipulate during the tandem rappelling and weight transfers than the original one. Conversely, the system shown would also allow for the knees and feet to be kept elevated throughout the self-rescue procedure, if needed. In his review article, Dr. Roger Mortimer makes a pretty convincing case that suspension trauma is quite different from crush/compartment syndrome. Having the legs elevated at all is not recommended for trauma patients. The issue is that you are not going to be able to elevate the legs at all times and when somebody had had significant blood loss, shifting blood from the core back to the legs can cause the patient to have a dangerous and quick drop in blood pressure that could kill them very quickly. This can happen even if you shift the legs down for a few seconds. Additionally the body needs gravity to return venous blood to the heart and this is screwed up if a person is leaned back. If your patient is unconscious they have sustained head trauma. Increasing blood pressure in the brain even more is really bad. To second what one guy said regarding airway...tongues are really really floppy in people who are unresponsive. Having them tilted back like that or even just laying flat is going to make it impossible to keep their airway open. The way folks are transported in the ambulance is semi fowlers position, look it up. Its done that way because its easier to breath sitting up than laying flat (supine). Your airway is more important than making sure this person doesn't receive trauma from hanging in the harness.

|

|

|

Buff Johnson

·

Oct 22, 2014

·

Unknown Hometown

· Joined Dec 2005

· Points: 1,145

The OP topic is just not very prevalent in life-threatening climbing injury and how rescues actually go down. Really, if the leader is unresponsive, it probably isn't because they scared themselves unconscious in a free fall, but that they hit something(s) really hard.

While 'suspension trauma' (not really trauma related) is an interesting phys topic, it's a rare occurrence and doesn't address the higher prevalence of head, c-spine, and other impact mechanism-related injuries more commonly seen in climbing.

Would the rigging setups in the OP's diagrams do more or less harm to the injured unresponsive climber in a buddy-rescue scenario as proposed?

Probably more harm.

One item I've seen more recently hammered on (I believe as also described in Dr. Mortimer's paper), don't delay body positioning when on the ground. There have been some repeated EMS articles that continue disseminating incorrect information about delaying a return of volume to the heart. Follow normal basic life support as you would in any other situation.

|

|

|

William Kramer

·

Oct 22, 2014

·

Kemmerer, WY

· Joined Jun 2013

· Points: 935

Also from my experiences in the field, the majority of head trauma calls I have been on may have been unresponsive for a short amount of time, but will regain a level of consciousness. Beware that it may be a very altered mental status, and typically they are very combative. This will definitely jeopardize safety for all involved for obvious reasons.

Another reaction from head trauma are seizures. Again a safety issue.

C spine is another hot topic in EMS right now, but as per protocol for the services I work for, and pretty much all other other services I know of, if the patient is unresponsive or of altered mental status, spinal immobilization needs to be done. Lowering the patient feet down vertical is the best way to accomplish this without having the proper equipment, bending the patient like in the diagrams does completely opposite of the purpose of this.

C spine is part of spinal, and that is might be tricky to accomplish in this kind of situation. Personally, I carry a small jump kit in my pack, including a SAM splint, folded instead of rolled to keep bulk down. Those things are great, great for splinting extremity fractures, but they can be turned into c collars as well. (They can also be used with a plastic grocery bag to make a water basin/sink)

|

|

|

Sam Latone

·

Oct 22, 2014

·

Chattanooga, TN

· Joined Dec 2012

· Points: 45

William Kramer wrote:the majority of head trauma calls I have been on may have been unresponsive for a short amount of time, but will regain a level of consciousness. The majority of head trauma calls I've run, the patients never regain consciousness and die several days later when their family takes them off the ventilator. These are car wrecks and falls from height...similar to impact forces your head experiences in a bad climbing fall. These patients almost always have a very poor outcome.

|

|

|

jktinst

·

Oct 23, 2014

·

Unknown Hometown

· Joined Apr 2012

· Points: 55

Thanks for these valid points. Unfortunately, they keep adding more contradictions. The Mortimer paper and HSE report are pretty clear in their recommendation to desuspend the victim to a flat surface and, yes, proceed with normal basic life support as you would in any other situation, ie do not leave the victim sitting up as has been recommended in various places. The semi-fowler position is not so far off horizontal and the suspension system shown in the position1 diagram could easily be adjusted to match it but the core question of whether adopting any position while remaining in suspension can significantly relieve the trauma remains unanswered.

Following the lead of the Mortimer paper, I looked at the suspension trauma in isolation, abstracting other potential traumas, while knowing that in a real life situation, other traumas would likely be present (except, perhaps, in the caving scenario of the victim succumbing to suspension trauma after becoming exhausted while ascending). Unfortunately, the combinations are endless so it's certainly likely to be a case of doing the best one can, trying to prioritise treatment of the most critical issues while avoiding as much as possible making the other ones worse (but also seems pretty likely to end up as a case of damned if you do & damned if you don't, especially since it is still unclear just how urgent suspension trauma is).

Given your profession, Mr. Kramer, I would strongly recommend that you read the Mortimer article. Again: it clearly states that suspension trauma is a very different beast from crush/compartment syndrome, requiring different handling in first aid, self- and organized rescue, etc. Based on that paper, placing the victim upright in his harness for the lowering, as you suggest, will inevitably accelerate the downward spiral of suspension trauma.

Regarding the floppy victim, the procedure to get a victim into a particular position while in suspension or prior to getting back into suspension starts by “capturing” with slings the target parts of the body before suspending them from the main suspension biner. In the case of position1 or any variant of it, I target just about everything: feet, knees, hands, elbows, torso and head. The cord running through the biners allows hoisting/lowering different parts to the correct position using the biner as a pulley before locking in place using Munter and Munter-mule-overhand. Unless I am grossly outweighed by the victim, I don't think that the floppy victim would be a big issue.

Since it appears that many people only look at the diagrams, I will update the two existing ones as soon as possible to call attention to the fact that there are strong indications that position2 is really not recommended and that position1 has also been called into question in the discussion. I am also tempted to illustrate what the semi-fowler position would look like in suspension but since I still don't know whether any position would help, I better not.

|

|

|

William Kramer

·

Oct 23, 2014

·

Kemmerer, WY

· Joined Jun 2013

· Points: 935

You're right, you can only do the best you can do given the situation. There are always reports and articles out there, does't mean they are gospel, put them in your mental toolbox as another tool that may be needed in a certain scenario.

And yes, I probably should look into suspension trauma more, but we are still trained to watch for crush/compartment. It takes a lot of study and proven results before something becomes an accepted thought or process.

As I said earlier, really did like your thinking with capturing the patient with slings and the thought process of why you did what you did, feel like it might be easier said than actually executed. We have a saying in this biz, KISS, Keep It Simple Stupid. Have to step back and re evaluate, rescuers have a natural tendency to over complicate things. And remember if you are in this situation, you will most likely be all jacked up, so simple is good at this time.

Thank you for this post. It has really got me thinking about some different things and now I have another tool in my toolbox, even going to try it out at our weekly training.

|

|

|

jktinst

·

Oct 23, 2014

·

Unknown Hometown

· Joined Apr 2012

· Points: 55

OK. The initial post has been updated. I hope I correctly summarized the main points but could correct further if needed.

William Kramer wrote:... KISS, Keep It Simple Stupid. Have to step back and re evaluate, rescuers have a natural tendency to over complicate things... Thank you for this post. It has really got me thinking about some different things and now I have another tool in my toolbox, even going to try it out at our weekly training. Setting aside the question of whether putting a victim in a particular position while remaining in suspension is actually beneficial, as I explained in the first post: the main practical issue with doing so is having a workable system to hold and adjust the head/helmet. I chose the dedicated sling. Sewing it would be the decidedly non-KISS aspect of the whole thing for most people, except, of course, once it’s made and available, using it is very much KISS. Before I opted for that, I worked out other options. The better one involved linking slings and duct-taping them to the helmet so that their 3 ends would poke just under the rim at both temples and at the back, to serve as guides for a suspension sling. This could be threaded in the same manner shown for the “factory-installed helmet mod” on the first diagram. Setting up this duct taped system is not fantastically KISS either but it’s really not that bad if you’ve tried it once or twice. The main drawback is that implementing it while in suspension leads to more jostling of the head than the dedicated sling. However, if implemented while the victim is lying down on a ledge in preparation for further rappelling, it becomes a more realistic proposition. Everything else (placing the slings on the other body parts and adjusting/setting the main suspension cord) may look complicated but is really not bad. As I said: in 3 tests (plus thinking through the sequence ahead of trying it), I had it down to 11-12 min. I felt that my posts were already long enough so I didn’t include the step-by-step sequence but I am happy to provide it (of course, these step-by-step sequences always look more complex at first glance than they really are).

|

|

|

Buff Johnson

·

Oct 23, 2014

·

Unknown Hometown

· Joined Dec 2005

· Points: 1,145

jktinst wrote: Setting aside the question of whether putting a victim in a particular position while remaining in suspension is actually beneficial...: the main practical issue with doing so is having a workable system to hold and adjust the head/helmet. ... trying to prioritise treatment of the most critical issues while avoiding as much as possible making the other ones worse .... Main points I found pertinent of the post were summarized for clarity. What we've used that is simple and more effective is a seated upright position with a c-collar -- Sam splint or designed. There's a good YouTube on the procedure for a Sam collar. I prefer the Sam in wilderness, I think it works really well around layered clothing. Then, instead of adding more rigs and levers on the shoulders, head, and neck, just get them positioned upright with a chest harness and rig a hitch to put their face into the rope. It keeps everything in alignment, and the collar protects both the c-spine and the airway. The overall concern in the OP's method is trying to bring a clinical solution that won't solve the main concerns of wilderness accident -- having a significant mechanism of traumatic injury. The method described in the OP will not keep everything in alignment, it can possibly make things worse. The only time I'd probably consider getting funky with body positions is industrial rope access, where they didn't have a fall from height, and just slumped over in their fixed-line rigging while they were working. Maybe jumaring up a fixed line -- big wall or gumby mountaineering. But a climbing lead fall (or getting tagged with rockfall), this topic isn't on the radar that would cause me to take another measure. Again, the unresponsive lead climber isn't unresponsive because of suspension trauma, something hit them or they hit something really hard. If you can't lower them quickly back you, then you'll have to consider head, c-spine, and airway protection as the priorities.

|

Continue with onX Maps

Continue with onX Maps Continue with Facebook

Continue with Facebook